What are the implications of the extensively documented fact that agents of the Soviet government were employed in high positions in the United States government in the 1930s and 1940s? Do we have a skewed view of World War II because we have failed to address that question? If our perspective changed, would we judge that we didn’t even win World War II – but, to be more accurate, Stalin did?

Diana West’s remarkable new book, American Betrayal: The Secret Assault on Our Nation’s Character, compiles some potential answers to these questions. As West argues early in the book, the American mind has become accustomed to the delinking of fact from implication – in large part, although we don’t see this connection, because of the troubled history of public revelations about Soviet infiltration of our government. She cites, as a model, the line of obfuscation that has protected the reputations of men like Alger Hiss, Robert Sherwood, and Harry Dexter White – all proven Soviet agents – by deflecting, not disproving, the fact that they were Soviet agents, while focusing attention elsewhere, typically on attacking the character and motives of those who exposed them.

But that line of obfuscation has done something even more important than blacken the names of Whittaker Chambers, Martin Dies, and Joseph McCarthy. It has succeeded in preventing three generations of Americans from considering the implications of the fact that our national government was infested with agents of the Soviet Union. What does it mean about our policies, that these men were so involved in making them?

World War II

West highlights some specific areas in which we may deduce what the implications were. Probably the easiest to prove is the nature of the Lend-Lease program. If you’re like me, you were taught in grade school that Lend-Lease was designed by Franklin D. Roosevelt to arm Britain for the fight against Hitler, since he couldn’t get the U.S. into the war in its first years. Some amount of support went to the Soviet Union, once we became allies. But the emphasis in educating America’s children on the program, in the decades since World War II, has been on the arming of Britain.

West’s research turned up a very different picture. Lend-Lease, whose biggest beneficiary was the Soviet Union, was a unique program which bypassed Congress to allow FDR to send arms wherever he thought best. Shortly after Hitler invaded the USSR in June 1941, Lend-Lease began heaving huge amounts of arms, supplies, and even intelligence on the United States at Moscow.

West provides evidence that Lend-Lease, besides creating a pipeline in which intelligence on U.S. military and industrial facilities could be funneled to the Soviet Union, was also the vehicle for providing American support to the USSR’s nuclear-weapons program – including a shipment of uranium to the Soviets honchoed in 1943 by Harry Hopkins, FDR’s closest advisor during the war.

But Lend-Lease did more than hemorrhage intelligence (and, as West also reports, facilitate the entry of Soviet spies into the U.S). Lend-Lease prioritized massive quantities of arms for the Soviet Union as well – prioritizing them over arms and supplies for U.S. and British forces.

Citing earlier sources – we have known these things for a long time – West outlines how aircraft and munitions flowed uninterrupted to the Soviets during the Battle of the Philippines in late 1941 and 1942, when Douglas MacArthur needed but could not get air reinforcements, and eventually had to evacuate, leaving the U.S. protectorate of the Philippines to its fate. Indeed, in the fall of 1941, a big shipment of 200 aircraft that was intended for the British forces defending Singapore was diverted to the Soviets in the Lend-Lease pipeline, along with a shipment of tanks. Singapore fell to the Japanese in February 1942.

FDR told U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau in March 1942 – incident to an appeal from MacArthur for support to the U.S. and Filipino troops fighting on Bataan and Corregidor – that he “would rather lose New Zealand, Australia, or anything else than have the Russian front [i.e., the front with Hitler in the western Soviet Union] collapse.”

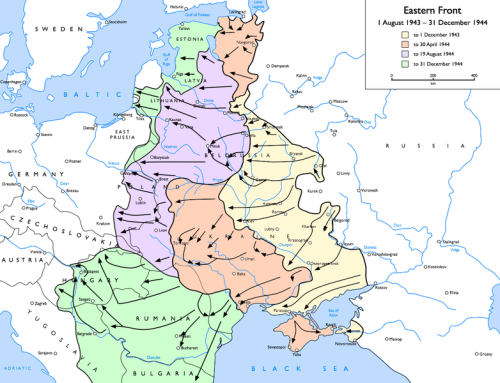

Was the Russian front in danger of collapsing? That’s a good question; by March 1942, Soviet troops had pushed the Germans back from Moscow and had them retreating toward Vitebsk, Smolensk, and Kursk along the northern portion of the front. Later, in August 1942, the Germans would launch Operation Blue and drive to their furthest point of advance into the Caucasus – almost to Grozny, in Chechnya – in the south. (The Battle of Stalingrad was part of this advance.) Hitler hoped to secure the Caucasus oilfields with this move, recognizing that with the United States in the war, his link to North Africa could be in increasing peril. (American troops landed in North Africa in November 1942.)

If there is a weakness in West’s treatment of her topic, it lies in the fact that she doesn’t fully address the war context in which FDR was making decisions (or, at least, his advisors were). She makes a very commendable effort to do just that regarding some of her points; e.g., regarding the Allied decision to conduct the D-Day invasion. On the question of how close the Russian front was to “collapse,” however, the book doesn’t outline a context for making that assessment in early 1942.

Stipulating that hindsight is not available to decision-makers, we can note that Soviet forces, reinforced from the Far East, and having received Lend-Lease supplies for at least six months at that point, had been able to mount a successful counteroffensive on the most strategically important 300-mile stretch of an 800-mile front. Moscow was in no danger of falling, by March 1942; whether any portion of the Soviet front line was in danger of “collapsing” – or, indeed, what FDR even meant by those words – is harder to say.

But West will get pushback on her book, from knowledgeable people of goodwill who have lived for many years with the standard narrative of World War II in their heads. If FDR prioritized supplying the Soviets over supplying U.S. and British forces in Southeast Asia, they will say, that was because of his war strategy: a strategy we have long known about and recognized as part of the narrative. What’s the big deal? Yes, we knew FDR decided to focus our effort on the European front first. Analysts and historians have been thrashing out the question of whether he should have for decades. Does West’s book add anything new?

The impact of Soviet influence

I find that it does: first, because it brings multiple events and threads of activity into focus at the strategic level, in a way most treatments of World War II have not; and second, because it emphasizes and inspects in detail the FDR administration’s focus on the Soviet front with Germany. In telling ourselves the narrative of the war, Americans have tended to gloss over that aspect of it. We have, moreover, focused on the great battles, typically painting in no more than a few contextual strategic strokes around them. What Diana West does, in effect, is survey the landscape of the war from that higher, strategic level, and ask, “Why?”

Building her case for Soviet penetration of the FDR administration, she points out that Harry Hopkins, he of the uranium shipment to the Soviets, took the extraordinary action in 1943 of personally warning the Soviets that the FBI had a particular Soviet agent under surveillance, after he was officially advised of that fact by J. Edgar Hoover. Also in 1943, the Soviet foreign minister, Maxim Litvinov, presented the White House with a list of individuals in the U.S. State Department whom the Soviets wanted removed from their positions – and within a couple of months, all of those individuals were gone. (These events are documented.)

Did this level of Soviet embeddedness in U.S. government operations have no consequences for our war-strategy decisions? Consider the context of the decision to mount the Normandy invasion in 1944 – after Allied forces in 1943 had driven into southern Italy and secured Rome’s surrender. Allied military planners at the time made a strong case for coming at Germany from the south, on the ground primarily through the Balkans in the East, and in the air, moving bases gradually closer from the redoubt of southern Italy, as well as flying from Britain across northern France. The Soviets were the loudest voice against this course, insisting that the new front must be opened from the northwest – that no other front opened anywhere would do the trick.

Now consider, as West asks, that in 1942, 1943, and 1944, high-ranking Germans who opposed Hitler made multiple overtures to the Western Allies to negotiate a German surrender: one that would in each case have involved removing Hitler from power while averting a Soviet advance into Germany. FDR stonewalled each one of these overtures, declining to respond in any way.

Meanwhile, Soviet propaganda themes, inaccurately reflecting German opposition groups as weak, corrupt, and feckless, were being faithfully repeated by an analyst at the German Desk of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the wartime intelligence agency. Franz L. Neumann wrote dismissive, pejorative intelligence assessments of the German resistance – because he was, in fully documented fact, a Soviet agent, working for the KGB. (As West notes, Neumann was also an early member of the “Frankfurt School” of Marxist social theory.)

Now reflect that in January 1943, when the Soviets were successfully driving the Germans out of the Caucasus – pushing back Hitler’s “Hail Mary” to get to the oilfields – while U.S. troops were fighting in Guadalcanal, New Guinea, and North Africa, and preparing for the invasion of Italy, Lend-Lease managers in the U.S. were given the following directive:

The modification, equipment, and movement of Russian planes have been given first priority, even over planes for U.S. Army Air Forces.Would the combination of these factors begin to color our view of “FDR’s strategy” to win World War II? In light of them, what exactly did “winning” mean to FDR? Why did FDR’s concept of winning World War II require that Stalin’s forces be armed for a drive across Eastern Europe? That was the basic end his policies all combined to serve.

Yet, objectively, it is entirely possible to conceive of an alternative strategy. Churchill had one in mind throughout the war, favoring the plan for the Western Allies to attack through the Balkans. Of course, the alternatives of either negotiating a German surrender before D-Day, or mounting a Western Allied drive through the Balkans, would have preempted the Soviet drive across Eastern Europe. There’s no escaping that fact, however else we explain FDR’s decision, or derive implications from it.

What happened in World War II was not fated; it was decided upon. There is nothing conspiracy-obsessed or insubordinate about second-guessing FDR’s strategy for World War II. The bottom line is that his strategy – his strategy – is what enabled Stalin to occupy Eastern Europe for the next 45 years. FDR not only gave Stalin the time and space to occupy Eastern Europe, he gave Stalin the means to do it. West quotes Khrushchev to the effect that Lend-Lease enabled the Soviet drive from Stalingrad to Berlin, but we don’t really need one-liners from Khrushchev to know that. Any objective analyst surveying the facts about the Soviet Union’s economy and overall situation would have to come to the same conclusion.

The American mind

Yet Americans have an entirely different narrative in our minds about World War II. With all the dense parade of facts and intensive footnoting in American Betrayal, its most powerful intellectual impact comes from West’s thesis: her abstract postulate about fact and implication. Why do we not recognize that FDR’s policies were designed to promote Stalin’s conquest of Eastern Europe, even though we know the basic facts that would cause us to at least consider the question? And what does that say about us?

Of most of the relevant facts, there was some level of public awareness at the time, or at least within a very few years afterward. There was no shortage of critics pointing out the consequences of FDR’s war policies. I recall as a teenager in the 1970s plowing through old books from the 1940s by James Burnham, the geopolitical analyst who in later life wrote for many years for National Review. Burnham – like many of the incisive anti-communists, a former socialist himself – foresaw very accurately in the mid-1940s what would happen to Eastern Europe, and why. West cites the critiques of others who understood, at the time, that the Allied victory in Europe in effect exchanged one brutal, collectivist hegemon for another.

But why Americans, in particular, wrote a different narrative about World War II and its aftermath remains an open question, I think. I don’t disagree with West that the Soviets and their handmaidens in the free world sought to influence our thinking about the war. The benefit to them from a deceptive narrative – one in which fact and implication never intersect except by their ideological approval – is obvious. But I think West gets at the most important factor of all without giving it the emphasis she gives to the panorama of Soviet-agent shenanigans. That factor is what, with our own free will, we chose to do.

The Reagan difference

I wouldn’t say on this topic that I part company with Ms. West’s analysis. But, having been a student of Ronald Reagan for so many years, I choose a different emphasis. Reagan behaved as if our motives and actions were what was most important. And by doing so, he achieved remarkable political successes at a time when Americans had been slowly buying, for over three decades, into a Soviet-serving narrative about social reality, World War II, and the trend of history.

Reagan would have agreed that, per the old military aphorism, the enemy – including the Soviet agent in the United States – always has a vote. The enemy’s actions and intentions do affect what we propose to do. But our decisions are ultimately governed by our priorities and attitudes, not the enemy’s.

Applying this axiom to the actions of the great majority of Americans who weren’t Soviet agents in the 1940s is something of an exploratory expedition into an undiscovered country. Perhaps the simplest explanation may turn out to be true: Soviet-sponsored lies about what was going on in Washington, D.C. were successful because the American people had so many other things in life to worry about. There were plenty of citizens – like my maternal grandparents – who distrusted FDR and supported the investigations of Communists in American institutions. But who had the leisure to turn this perspective into a politically successful movement?

I think there is truth to the case West and others make that the U.S. and the West didn’t defeat communism. But the U.S. did defeat the Soviet Union, and did thereby win the Cold War. Doing so dealt a body blow to communism as an organizing rubric for international predation. The reason why is something Reagan recognized clearly – just as Stalin recognized it, if for a morally opposite purpose: that ideologies and beliefs must hold territory, if they are to thrive and wield power.

Reagan turned the battle against a predatory communist ideology into an offensive struggle for the enemy’s own key territory – and Reagan was sure that we would win the struggle, because he took as a given that the evils of communism would be rejected wherever people were afforded a meaningful choice. He was right. His accurate prediction was not, moreover, about populations that had the unique libertarian characteristics of the United States, but about peoples who had never been as free, nor dreamed of being as free, as Americans have. Indeed, they were people who had been intensively indoctrinated for decades in Big Lies. There was hope even for them.

This matters because Reagan is the great exception to the rule that collectivism in its various guises – communism, fascism, Nazism, socialism, progressivism; “liberal fascism,” as Jonah Goldberg calls it – has been winning a war of attrition against the spirit of classical liberalism for the last 100 years. Not only did Reagan strike a death blow to Soviet communism – which no longer exists as an organized global predator – but his public, in liberated Eastern Europe as in America, remembers him accurately as having done so. At least for now, Reagan has beaten the odds against the liberal-fascist framing of history, which is more than can be said for the narrative of World War II.

The conflict of visions

The question is how to relate that to the problem Diana West propounds. In the larger context of our effective abandonment of logic, fact, and implication, the governments and reigning public ideas of the Western Left have come to resemble 20th-century communism to such an extent that there seems no point in distinguishing between them. Who really won World War II, after all, if the European Union is as ideologically collectivist as the old Soviet Union? Who really won the Cold War, if America is in the last stages of collectivization as I write, even though the old Soviet Union is gone?

Here again, I think West brings forth an important idea. She frames the conflict between collectivism and classical liberalism as one in which the body of Western beliefs – being open to evidence and not consciously ideological – has been somewhat defenseless in the face of a well-organized ideology. In her formulation, Western liberalism is not an ideology. Therefore, it doesn’t fight like one.

I don’t think this fully explains the imbalance of momentum between the two, however. I agree with West in fingering the ideological struggle as a point of vulnerability for the West. But I’m not convinced the distinction she proposes fully captures the issue. Must Western ideas be fated to extinction because they are subject to skepticism and empiricism, and are perhaps, therefore, reversible? If they were, how could they have survived up to now?

Again, Reagan suggests the answer, if we are willing to see it. Western liberalism is actually backstopped by irreducible assumptions, not just about the sanctity of human rights and dignity, but about the positive power of releasing our fellow men to liberty – if we base it on the Judeo-Christian idea of a merciful and provident God, one who designed us for good. Take God away, and our beliefs are backstopped only as far as the next election. Skepticism and lack of belief demonstrably do not stand up effectively against collectivist ideology as an organizing principle for communal life. But that does not mean that rational liberalism can’t. The question is what its foundation is.

There will be some who disagree with this last point. But it remains the case that the only U.S. president who changed our policies and achieved a different outcome in the Cold War was the one who philosophized about freedom – unabashedly, and often – from the perspective of this Judeo-Christian belief about God. Reagan followed in the footsteps of a line of Western philosophers, including America’s founders, for whom it was not empirical uncertainty but philosophical certainty, based on their understanding of God, that made them insist on limiting government’s collectivist imperative and privileging the individual over it. It was because of his belief in God that no Big Lie could confound Reagan on the topics of individual freedom and the evils of communism.

He was called the “Teflon president” in part because he spoke right past the Big Lies, as if they had never been told and needed no refutation. Reagan wasn’t known for debunking the Big Lies of communism. He was known for the positive ideas he espoused: freedom, limited government, the liberation of captive peoples. His political success amounted to an occupation of territory, a sort of reversal of Diana West’s “Soviet occupation” of Washington, D.C.: he simply took over the reigning political narrative, rather than fighting against someone else’s.

His success was by no means total, of course, even inside the United States, where entrenched bureaucracies guaranteed, before he was even sworn in, that Big-Lie narratives would outlast the Reagan tenure in the Oval Office. The seeds had been sown much earlier of the “governmentism” that would imperil Reagan’s purpose, and make it seem almost impossible that his impact would be enduring. West is right to warn that the overall course of the American ship of state has not really changed since at least 1933.

The cycle of history

But does this signify that the Reagan difference was meaningless? What I would propound, to frame this issue, is a pattern of human tendencies against which the liberal-minded of each generation are always battling. We – Americans, especially, but all Westerners to some extent – are apt to imagine a progressive quality to human affairs, one in which the battles we win need not be fought again. In this imagined context, Reagan’s victory over the Soviet Union settled the great question of the 20th century, collectivism versus liberty, once and for all.

But if we understand that the same old threats and complaints keep arising from human nature, and only the technology and slogans change, we can see more clearly that battles can be won and they do matter, but that they will have to be fought again and again – if sometimes on different ground.

There was nothing really new about the motives of Soviet communism, and not all that much new about its methods. Technology enabled the Soviets, as it did the Nazis, to scale new heights of effectiveness. But the urge to corral, organize, and dictate to one’s fellow men – and to do it in large part by subverting people’s perceptions and decision matrices – has always developed along the same old lines, from the Jacobins back through the schemers of late-Imperial Rome to the verbose demagogues of ancient Athens.

It isn’t possible to breed, train, or legislate this urge out of humankind. It can only be perpetually guarded against; or, even better, preempted – temporarily, within a given generation. As satisfying as the rare game-changing victory is – e.g., the founding of the United States, the victory over the Soviet Union – it is never “Game over” for the human urge to power. We will have to fight the fight again. What we must learn is not only how the collectivist enemy works, but what we have done in the past that was successful.

West is undoubtedly right about the resurgence of the Big Lie method, with Islamist advocacy in the U.S. government, academy, and media. And she is right that the less we understand what’s going on with it, the more our minds are corrupted by its deceptions, and by the rampant disconnects in its narrative between fact and implication.

Preparing the battlefield

I find reason for optimism, however, in what Reagan was able to accomplish in ending the Cold War. Reason for optimism, and a glimmer of the answer to our current problem with the Big Lie. As important as intellectual hygiene is, people don’t really navigate their way to positive, life-giving beliefs through the systematic debunking of lies. That’s not how we have our minds renewed. In fact, getting the perspective of wisdom and sound judgment on Big Lies typically requires having solid prior beliefs about what is good and right. Without those beliefs, recognizing the Big Lies just drives us to despair.

But the incandescent ideas of liberty, small government, and natural rights are still there, having been formulated for us and left to us as a priceless legacy by our forebears.

We can’t expect others – certainly not those in the Islamic world – to want our ideas if we are not living by them. We can expect that our heritage of ideas will be incessantly attacked and lied about, as it has been for at least 150 years by the communists and liberal fascists.

But if we emphasize speaking the truth about those ideas, at least as much as we emphasize debunking the Big Lies around us; and if we decide to live by the ideas again, rather than only pretending to do so and then misunderstanding the results that come from that pretense – if we will do those two things, we will, perforce, set up another war for territory between good and evil. It may or may not have to be waged on our own territory. That will depend on how soon we correct our course. But, as Reagan demonstrated, a war for territory – a war to occupy territory with the positive benefits of true liberalism – is a war we can win.

In the meantime, read Diana West’s American Betrayal. It is well worth your time. It will make you see the present with fresh eyes, as well as the past – even if, like me, you started out aware already of the Soviet agents and the contemporary criticism of FDR’s war policies. American Betrayal relies on extensive documentation, but it is a polemical work: it is meant to change your mind. And it will.

See here for a video of Diana West’s talk about American Betrayal for Children of Jewish Holocaust Survivors in Los Angeles on 10 July 2013.

J.E. Dyer’s articles have appeared at Hot Air, Commentary’s “contentions,” Patheos, The Daily Caller, The Jewish Press, and The Weekly Standard online. She also writes for the new blog Liberty Unyielding.

Note for new commenters: Welcome! There is a one-time “approval” process that keeps down the spam. There may be a delay in the posting if your first comment, but once you’re “approved,” you can join the fray at will.

No comments:

Post a Comment