The top priorities of ECHR concerns are matters such as Abu Qatada's "right to a family life." This change meant that he could not be sent somewhere where all these lovely new rights would not be afforded to him.It was impossible not to smile watching the footage of Abu Qatada in his specially-chartered private jet finally taking off from the UK for his home country of Jordan to face trial on terrorism charges.

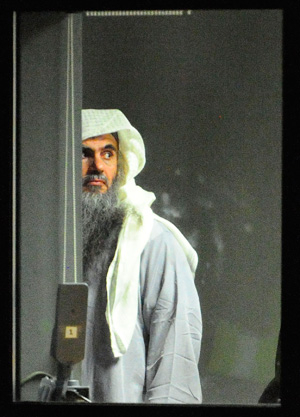

Abu Qatada moments before his deportation, July 7, 2013. (Source: UK Home Office)

|

In February 2001, Qatada was arrested at his home; police found £170,000 in cash there. Also in the house was £805 pounds in an envelope labelled, "For the Mujahedin in Chechnya." Then came 9/11, and when eighteen recordings of Abu Qatada talks were found in the Hamburg flat of the leader of those attacks, Muhammad Atta, the police acted. It had taken a long time, but Abu Qatada was finally in trouble.

For more than a decade, he then caused the most appalling headaches for successive home secretaries. One thing more than any other was the cause of this: by this time, the Labour government of the day had signed Britain up to the European Convention on Human Rights, a Convention that bound Britain -- by no further means than an over-reaching court and a certain amount of peer-pressure -- to abide by a wholly new standard of "rights."

So for instance where previously national security could be said to be an over-riding right, indeed concern, it now found itself somewhat lower-down the list of things to trouble government. The top priorities of ECHR -- and thus British -- concerns are matters such as Abu Qatada's "right to a family life." These rights were not just rights which Britain must provide to Qatada. They were rights which must be protected as long as he stayed in Britain, and which must be protected if any other nastier, non-ECHR-signing government were to express any interest in him. This change meant that Qatada could not be sent somewhere where all of these lovely new rights would not be afforded to him. Such as, unfortunately, Jordan -- which happened to be the one country that really wanted him.

Although the Jordanian authorities repeatedly requested that Qatada be deported to face justice there, it proved a stalling point. Although Britain continued -- rightly -- to regard the country as one of the better powers in the region, Jordan nevertheless turned out not to be such a friend that we could trust it with one of its own home-grown terrorists.

The European Court -- which batted the Qatada case back and forth with successive UK governments -- insisted first of all that it was most important that Qatada not be sent back to Jordan finally to face up to the terror charges against him because if he did, he might be mistreated in some way. At significant cost of expense and time, the British government agreed to a memorandum of understanding with the Jordanian authorities precisely to ensure that Qatada would not be mistreated. The Jordanian authorities gave their assurance.

But then members of the ECHR moved the goalposts. On the next expensive to-and-fro, they decided that nobody whose evidence might be heard at a future Qatada trial in Jordan could be someone who might have been treated in a manner deemed unacceptable by the ECHR. And so it went on and on.

Most of us had simply expected to grow old with Abu Qatada alongside us. He was, after all, in and out of the maximum security Belmarsh prison. Some of the time this went well. Other times he was found consorting with people he oughtn't to have been consorting with, and back in he went. Just recently he was re-arrested after the discovery of extremist material in his home. Who would have guessed?

For all this time, of course, Qatada was a desperate embarrassment to the state. But once Britain signed up to the ECHR, we became governed not by politicians but by lawyers. And they had great fun frustrating multiple Home Secretaries, exploring every available option to keep him in the UK.

In recent months the current Conservative Home Secretary, Theresa May, again travelled to Jordan to receive further assurances and to sign further memoranda with the Jordanian authorities. And this time, after only a couple of decades, several million dollars and egg all over the British state and its new laws, the Qatada extradition finally occurred and is being hailed as a triumph of justice.

Of course it is extremely good to be rid of him. I hope he has a nice time in Jordan. But nobody can look back on recent years and think this has been anything but a farce. Tough cases make bad laws, they say. But Qatada was not a tough case. He was an easy case. We should have been rid of him years ago. The fact that we weren't -- and are never likely swiftly to rid ourselves of a Qatada-type again -- is the only cloud in the sky into which we waved him off.

No comments:

Post a Comment