Martin Kramer

Martin Kramer says: On March 4, a curious video clip from Syria appeared on the internet. It

shows a large, gilt-framed double

portrait of Ayatollahs Khomeini and

Khameneh’i cast down on a stone floor. A

man whose face is never shown steps

repeatedly on the portrait, to the

crunching sound of broken glass. Four

times in the 90-second segment, the

camera pans up to focus on the ornate

portal of an impressive building,

inscribed with a verse of the Qur’an

(13:24): “Peace unto you for that ye

persevered in patience! Now how

excellent is the final Home!” Someone

off-camera mutters the name of Raqqa, a

dusty provincial capital situated on the

Euphrates about 200 kilometers east of

Aleppo. It was seized by Sunni Islamist

insurgents during the first week of

March, and this clip clearly depicts an

episode in the immediate aftermath of

the city’s capture. But it does not

identify the specific place or explain

the act of iconoclasm it depicts.

Martin Kramer says: Had the camera panned up still further,

it would have revealed the entire façade

(shown in the photo on the right),

completing part of the puzzle. The upper

inscription identifies this site as the

shrine of two figures from

seventh-century Islamic history, Ammar

ibn Yasir and Uways al-Qarani. The

façade is striking, but just what is the

connection of this shrine in Raqqa to

Ayatollahs Khomeini and Khameneh’i, and

why is their portrait being defaced at

its entrance?

As we shall see, the answer to that question establishes the short video clip as one of the most significant images to emerge from Syria’s civil war. It proclaims that the so-called “Shiite crescent” is now eclipsed.

(In the following commentary, I have relied heavily on the work of Myriam Ababsa, a research fellow in social geography at the Institut français du Proche-Orient in Amman, Jordan. References to her publications are linked from the last photo in this essay.)

(All the video clips linked from this gallery are embedded on one convenient page, here.)

As we shall see, the answer to that question establishes the short video clip as one of the most significant images to emerge from Syria’s civil war. It proclaims that the so-called “Shiite crescent” is now eclipsed.

(In the following commentary, I have relied heavily on the work of Myriam Ababsa, a research fellow in social geography at the Institut français du Proche-Orient in Amman, Jordan. References to her publications are linked from the last photo in this essay.)

(All the video clips linked from this gallery are embedded on one convenient page, here.)

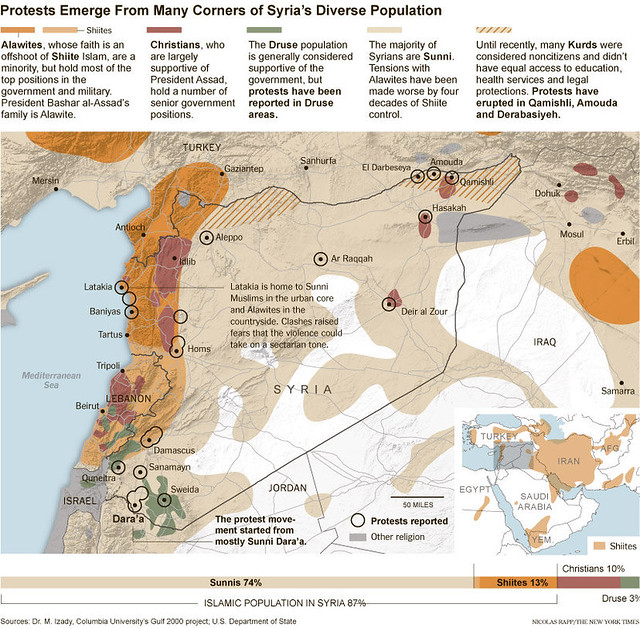

Martin Kramer says: The notion of a "Shiite crescent"

stretching from the Persian Gulf to the

Mediterranean has always been

problematic, for a very simple reason.

While there are millions of Shiites in

Iraq and Lebanon, the swath of territory

along the middle Euphrates in Iraq and

Syria is entirely Sunni.

Mindful of this vulnerability, Iran decided in the 1980s to raise the profile of Shiism in Syria, with the cooperation of the Syrian regime. The driver was the strategic relationship between Syria and Iran, dating back to Iran's 1979 revolution. In support of this relationship, Iran and Syria collaborated to forge cultural and religious ties. Syria has only about 100,000 Twelver Shiites (of the same denomination as those in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon). But the pillars of the Asad regime (above all, the Asads themselves) hail from the Alawite sect, two or three million strong, which in recent decades has presented itself as a variety of Shiite Islam. Against this background, Syria and Iran worked together to bolster Shiite influence in Syria, as part of a strategy to legitimate the Iran-Syria bond and the Shiite standing of the Alawites.

Mindful of this vulnerability, Iran decided in the 1980s to raise the profile of Shiism in Syria, with the cooperation of the Syrian regime. The driver was the strategic relationship between Syria and Iran, dating back to Iran's 1979 revolution. In support of this relationship, Iran and Syria collaborated to forge cultural and religious ties. Syria has only about 100,000 Twelver Shiites (of the same denomination as those in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon). But the pillars of the Asad regime (above all, the Asads themselves) hail from the Alawite sect, two or three million strong, which in recent decades has presented itself as a variety of Shiite Islam. Against this background, Syria and Iran worked together to bolster Shiite influence in Syria, as part of a strategy to legitimate the Iran-Syria bond and the Shiite standing of the Alawites.

Martin Kramer says: Part of this campaign involved Iran's

renovation or construction of major and

minor shrines across Syria. These were

either Shiite by tradition or could be

rebranded as Shiite. In this plan, Raqqa

loomed large.

Raqqa is thoroughly embedded in the solidly Sunni territory stretching from the Syrian-Iraqi border at Abu Kamal westward to Aleppo. Iran chose it as the place to implant a kind of frontier outpost of Shiism, both because of its geographic position and the presence of the tombs of two legendary figures claimed by Shiites as champions of their cause.

Iran’s promotion of Shiite shrines in Syria has been most intensive in the vicinity of Damascus (the mausoleums of Sayyida Zaynab and Sayyida Ruqiyya). Damascus is home to a large Iranian embassy and an elaborate infrastructure to service Iranian and other Shiite pilgrims. It is also within easy reach of Lebanon's Shiites as well as Hezbollah, Iran's client militia. But Raqqa is far from any Shiite population and stands well off the beaten path of Iranian pilgrimage. The plan for the Raqqa shrine thus constituted an instance of aggressive Iranian penetration of a Sunni preserve, with the intent of creating a Shiite and Iranian presence where none had existed before.

Raqqa is thoroughly embedded in the solidly Sunni territory stretching from the Syrian-Iraqi border at Abu Kamal westward to Aleppo. Iran chose it as the place to implant a kind of frontier outpost of Shiism, both because of its geographic position and the presence of the tombs of two legendary figures claimed by Shiites as champions of their cause.

Iran’s promotion of Shiite shrines in Syria has been most intensive in the vicinity of Damascus (the mausoleums of Sayyida Zaynab and Sayyida Ruqiyya). Damascus is home to a large Iranian embassy and an elaborate infrastructure to service Iranian and other Shiite pilgrims. It is also within easy reach of Lebanon's Shiites as well as Hezbollah, Iran's client militia. But Raqqa is far from any Shiite population and stands well off the beaten path of Iranian pilgrimage. The plan for the Raqqa shrine thus constituted an instance of aggressive Iranian penetration of a Sunni preserve, with the intent of creating a Shiite and Iranian presence where none had existed before.

Martin Kramer says: Raqqa's great moment in history came in

the late 8th century, when for a dozen

years it was the base of the caliph

Harun al-Rashid and the capital of the

vast Abbasid empire. It has not been

continuously inhabited, and it was

totally abandoned for much of the

Ottoman period, until its resettlement

in the late 19th century. Since Syrian

independence it has grown rapidly, and

in normal times it is home to almost a

quarter of a million inhabitants. Tribal

identities still matter in Raqqa, whose

inhabitants have been urbanized only in

the last few generations. The population

in and around the city is

diverse—townspeople, Bedouin, and

herding tribes (shawaya)—each part of which stands in a

different relationship to the central

government and the regime. The province

as a whole has seen much environmental

degradation, and In recent years the

countryside has been ravaged by severe

drought.

Martin Kramer says: At the core of the shrine plan stood two

ancient tombs, supposedly holding the

remains of two "martyrs" of

the battle of Siffin (657) who fought alongside the

Prophet's son-in-law Ali against

Mu'awiya, the governor of Damascus and

founder of the Umayyad dynasty. (Siffin

is forty kilometers west of Raqqa.) One

of the fallen was Ammar ibn Yasir, a contemporary and companion of the

Prophet Muhammad; the other was Uways al-Qarani, an ascetic Yemeni camel-herder with

whom the Prophet is said to have

communicated by telepathy. The

identification of their tombs at Raqqa,

relying on traditions, is conjectural.

(Uways also has final resting places in Yemen, Turkey, Iran, Egypt and elsewhere.)

The model in this photo, displayed today inside the shrine, shows the original scheme of the complex. A mosque houses each of the two tombs, and each mosque is flanked by a minaret. The two mosques are linked by an arcaded courtyard. (The symmetry is broken by the minor tomb of Ubayy ibn Ka'b, a secretary to the Prophet Muhammad, on the far left.)

The model in this photo, displayed today inside the shrine, shows the original scheme of the complex. A mosque houses each of the two tombs, and each mosque is flanked by a minaret. The two mosques are linked by an arcaded courtyard. (The symmetry is broken by the minor tomb of Ubayy ibn Ka'b, a secretary to the Prophet Muhammad, on the far left.)

Martin Kramer says: The original tombs, simple affairs, were

situated in an old cemetery on the edge

of the river's flood plain. (A photo from 1924 shows the then-existing

cupola of Uways and the cemetery on the

far right.) From the 1960s, all the old

cemeteries of Raqqa were moved to allow

for urban development, with the

exception of the cemetery of the Siffin

"martyrs." In 1988, the

authorities laid down concrete slabs

over the tombs of Ammar and Uways, and

instructed local families to remove

their own dead to another cemetery, five

kilometers away.

Here a sign on the work site announces (in Arabic) that the building project is sponsored by the Islamic Republic of Iran, and is under the supervision of the Iranian Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.

Here a sign on the work site announces (in Arabic) that the building project is sponsored by the Islamic Republic of Iran, and is under the supervision of the Iranian Ministry of Housing and Urban Development.

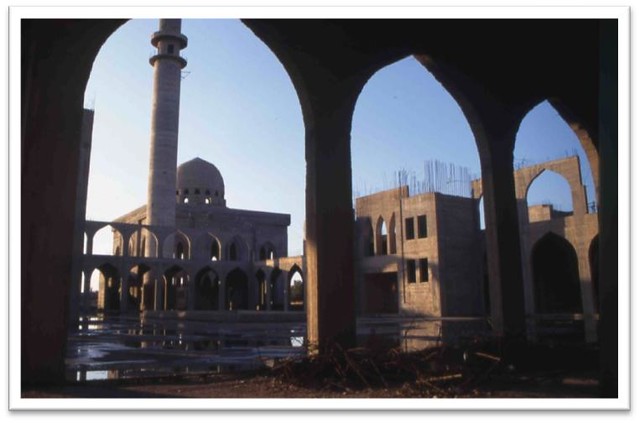

Martin Kramer says: Construction commenced in 1988, but was

halted between 1994 and 2001. Differing

explanations were offered, including

disputes between Syrian and Iranian

authorities over financing, and local

Sunni opposition. This photograph was

taken in 1997 during that hiatus.

Martin Kramer says: The construction was finally completed

in 2003. (This photograph was taken in

2005, from precisely the angle of the

1997 photograph above.) A dedicatory plaque (in Persian) at the entrance to the

complex credits Ayatollah Khomeini and

President Hafez Asad with initiating the

project, and Ayatollah Khamaneh'i,

President Bashar Asad, and

then-president of Iran Mohammad Khatami

with bringing the project to a

conclusion. The architectural style of

the structure is neo-Safavid,

implemented with an attention to lavish,

over-the-top detail that signals the

power and wealth of the Iranian patron

state.

An excellent feel for the shrine in context is provided by a short two-part video travelogue (in Arabic), in which a guide pays a visit to the shrine, driving first to and through Raqqa (part 1), then entering the shrine and paying particular attention to the mausoleum and the legacy of Ammar ibn Yasir (part 2). (He makes no mention of Iran.)

An excellent feel for the shrine in context is provided by a short two-part video travelogue (in Arabic), in which a guide pays a visit to the shrine, driving first to and through Raqqa (part 1), then entering the shrine and paying particular attention to the mausoleum and the legacy of Ammar ibn Yasir (part 2). (He makes no mention of Iran.)

Martin Kramer says: The tomb of Ammar ibn Yasir is favored

by foreign pilgrims, above all the

Iranians, but also other Shiites, who

regard him as one of the four most loyal

adherents of Ali. The women make vows

and tie bits of green cloth to the

silver grating, which they kiss and

caress. This video clip, shot within the mausoleum, conveys the

new splendor in which Ammar's remains

now lie.

Martin Kramer says: The mausoleum of the mystic Uways,

bathed here in an eerie green, has much

resonance for Raqqawis. His supposed

tomb had been a place of visitation and

cultic veneration for the region's

tribes over some centuries, even when

Raqqa itself was desolate. Still,

Raqqawis do not identify him as a

"Shiite martyr," but as an

intercessor who symbolizes their

autonomy. Local women traditionally

visit the tomb to ask Uways to intercede

and provide them with husbands and

children. Notes of supplication tossed

through the grate are visible on the

left side of this photo. This video clip shows women pilgrims clustered around

the tomb of Uways.

Martin Kramer says: Raqqa is surrounded by semi-settled

tribes, some branches of which believe

they are descended from Husayn, the son

of Ali and grandson of the Prophet

Muhammad, who is the central figure of

Shiite martyrology. They sometimes

belong to Sufi orders that venerate Ali

and Husayn. Unlike the city dwellers,

who regarded the shrine project with

surly resentment, they welcomed it as a

kind of beautification project. They are

Sunnis, not Shiites, but they seemed

like promising targets for Iranian

proselytization. Visiting Iraqi or

Iranian preachers would bring them

together at the shrine for sessions

commemorating their supposed forebears (majalis husayniyya). Some were invited to Iran as guests

of the state. Actual conversion of

Raqqawis to Shiism is reported to have occurred infrequently, although

there is widespread suspicion that the ultimate purpose of the shrine

was promote just that.

Martin Kramer says: Raqqa during the 1990s and 2000s also

witnessed a cavalcade of events

sponsored by Iran, consisting of

conferences and lectures devoted to

Shiite themes and Iranian-Syrian comity.

Ayatollah Muhammad Husayn Fadlallah,

then the preeminent Shiite cleric in

Lebanon, spoke on several occasions, and

Hezbollah and Iran used the shrine as a locus of mobilization.

In 2002, at the height of the second

Palestinian intifada, the Iranian

cultural office in Aleppo organized a

"day of solidarity" at the

shrine, reportedly attended by 5,000

people. What Iran could not achieve in

the sphere of religion, it thought to

gain by emphasizing Iran's steadfast

solidarity with the Syrian regime's

"resistance" to Israel.

Martin Kramer says: The boom in Iranian pilgrimage to Syria

dates back to the 1980s. The Shiite

shrines of Iraq in Najaf and Karbala

became inaccessible to Iranians

following the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq

war in 1980. Emphasis shifted to the

pilgrimage to Mecca, where Iranian

pilgrims combined religious observance

with political demonstrations. But in

1987, Saudi police clashed with demonstrating Iranians in Mecca's

streets, killing over 400, and the

Saudis barred Iranians from making the

pilgrimage. The Shiite shrines of Syria,

which had not been major attractions for

Iranian pilgrims, gained unprecedented

importance in the absence of other

options.

After the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iranian planners conceived an ambitious plan for a kind of pilgrimage trail, consisting of a chain of shrines from Karbala to Damascus. Following the battle of Karbala in 687, the Umayyad caliph Yazid ordered that the head of the defeated Husayn be brought to him in Damascus. The idea was to create a route of pilgrimage following the stations of the head's journey, anchored at the midway point by the already existing shrine to Husayn in Aleppo. To this end, Iran began to invest in the renovation and expansion of other sites in Syria.

Still, a scholar who has studied the entire range of Iranian shrine projects in Syria has written that, more than any other such effort, the Raqqa shrine "best represents the extent of Shiite triumphalism and state support in Syria."

(A photo shows a line of buses carrying Iranian pilgrims lined up outside the Raqqa shrine.)

After the fall of Saddam Hussein, Iranian planners conceived an ambitious plan for a kind of pilgrimage trail, consisting of a chain of shrines from Karbala to Damascus. Following the battle of Karbala in 687, the Umayyad caliph Yazid ordered that the head of the defeated Husayn be brought to him in Damascus. The idea was to create a route of pilgrimage following the stations of the head's journey, anchored at the midway point by the already existing shrine to Husayn in Aleppo. To this end, Iran began to invest in the renovation and expansion of other sites in Syria.

Still, a scholar who has studied the entire range of Iranian shrine projects in Syria has written that, more than any other such effort, the Raqqa shrine "best represents the extent of Shiite triumphalism and state support in Syria."

(A photo shows a line of buses carrying Iranian pilgrims lined up outside the Raqqa shrine.)

Martin Kramer says: In the first week of March, Raqqa fell

to a coalition of Islamist insurgents led by Ahrar al-Sham. The city had not been a seat of

resistance to the regime, and in fact

had been flooded by refugees fleeing the

fighting elsewhere. As recently as

November 2011, Bashar Asad had made a

demonstrative visit to the city, which had remained loyal.

Perhaps for that reason, Raqqa had been

under-garrisoned, and in a bold move,

insurgents overran it with little

fighting, taking the city intact. The

insurgents brought down the statue of

Hafez Asad in the town center and

established a rudimentary civil

administration.

This photograph from the central square shows the toppled statue. In the background, the green graffiti announces the fall of the "dog of Iran," alongside the name of Jabhat al-Nusra, the most extreme branch of the Sunni opposition to the regime. It is Jabhat al-Nusra that reportedly seized the Raqqa shrine and turned it into a headquarters for issuing fatwas. (Another report claims it is being protected by tribesmen.)

This photograph from the central square shows the toppled statue. In the background, the green graffiti announces the fall of the "dog of Iran," alongside the name of Jabhat al-Nusra, the most extreme branch of the Sunni opposition to the regime. It is Jabhat al-Nusra that reportedly seized the Raqqa shrine and turned it into a headquarters for issuing fatwas. (Another report claims it is being protected by tribesmen.)

Martin Kramer says: This, then, is the context of the video

clip showing Ayatollahs Khomeini and

Khameneh'i underfoot. They had conceived

and promoted this outpost of Shiism and

Iran in the heartland of Sunni Islam.

The Asad regime had imposed it with the

aim of bridging the gap in the

"Shiite crescent." With the

capture of Raqqa by insurgents, the

plans of Iran and the regime have come

undone. Nowhere in Syria are there

statues of Iranians to be toppled. But

there are other icons to smash, and the

breaking of this one in Raqqa has as

much significance as the toppling of

Hafez Asad's statue.

What will become of the shrine itself is uncertain. A false Iranian report claimed it had been destroyed by Sunni extremists, but that didn't happen and it is unlikely to happen, since veneration of the tombs was a local tradition even before the Iranians arrived. The site is likely to be purged of its explicitly Iranian and Shiite references, but it is impossible to know which symbols will replace them.

It could be any one of the flags now sold in Raqqa, as shown in this photo. From right to left are the flags of the Free Syrian Army (minimally present in Raqqa), Ahrar al-Sham (dominant), and the black-and-white variations of the jihadist flag flown by Jabhat al-Nusra (also a major force). The struggle that will elevate one of these symbols over the others has only just begun.

What will become of the shrine itself is uncertain. A false Iranian report claimed it had been destroyed by Sunni extremists, but that didn't happen and it is unlikely to happen, since veneration of the tombs was a local tradition even before the Iranians arrived. The site is likely to be purged of its explicitly Iranian and Shiite references, but it is impossible to know which symbols will replace them.

It could be any one of the flags now sold in Raqqa, as shown in this photo. From right to left are the flags of the Free Syrian Army (minimally present in Raqqa), Ahrar al-Sham (dominant), and the black-and-white variations of the jihadist flag flown by Jabhat al-Nusra (also a major force). The struggle that will elevate one of these symbols over the others has only just begun.

Martin Kramer says: Raqqa is being watched as a model of how hardline Islamists might

administer a free Syria, but its fall is

hardly decisive for the fate of the

country as a whole. Syria's future will

be determined along the central axis

leading from north to south, from Aleppo

to Dara'a, and ultimately to Damascus.

The Shiite shrines near Damascus are far

more important to the survival of the

Shiite link through Syria, and there are

many reports that Shiites from Lebanon and Iraq are

fighting to protect them. The Raqqa

shrine was too isolated to be defended

in such a manner.

Although many videos stream out of Raqqa daily, only one has shown the Raqqa shrine. Perhaps the insurgents believe that broadcasting such images would only serve to mobilize foreign Shiites for the ongoing battle for Damascus, particularly around its shrines. No one knows how that battle will end, or what the future holds for Iran in Syria. But for now, the "Shiite crescent"—a romantic fantasy of towering minarets and blue domes in lands of Shiite legend—has been eclipsed by the black smoke of Syria's war.

End.

Although many videos stream out of Raqqa daily, only one has shown the Raqqa shrine. Perhaps the insurgents believe that broadcasting such images would only serve to mobilize foreign Shiites for the ongoing battle for Damascus, particularly around its shrines. No one knows how that battle will end, or what the future holds for Iran in Syria. But for now, the "Shiite crescent"—a romantic fantasy of towering minarets and blue domes in lands of Shiite legend—has been eclipsed by the black smoke of Syria's war.

End.

Martin Kramer says: The only accounts of the Raqqa shrine

are provided by Myriam Ababsa, in a

chapter in her book on Raqqa (here) and in two other articles (here and here). While there is some overlap among

these studies, each one adds something

of unique value. My reliance on the

wealth of detail in these studies has

been almost total.

For related reading on the larger Iranian and Shiite project for Syria, see studies by Sabrina Mervin (here), Yasser Tabbaa (here), Paulo G. Pinto (here), and an anonymous monograph in Arabic (here).

For the most interesting images now coming out of Raqqa, consult @beshroffline. For the latest videos, visit this Youtube channel.

For related reading on the larger Iranian and Shiite project for Syria, see studies by Sabrina Mervin (here), Yasser Tabbaa (here), Paulo G. Pinto (here), and an anonymous monograph in Arabic (here).

For the most interesting images now coming out of Raqqa, consult @beshroffline. For the latest videos, visit this Youtube channel.

No comments:

Post a Comment