: theoptimisticconservative | December 23, 2013

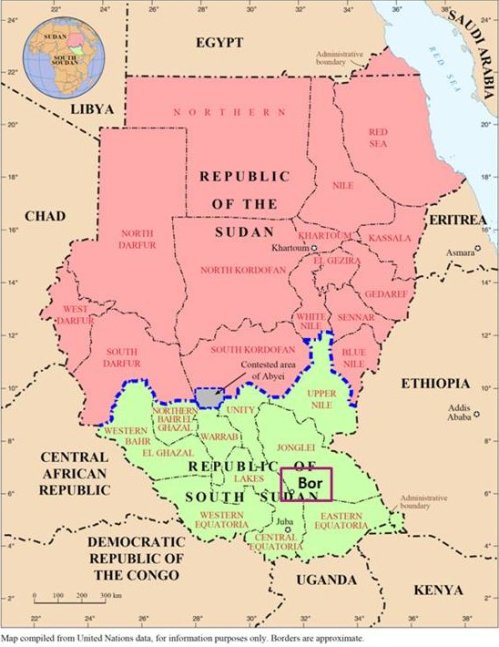

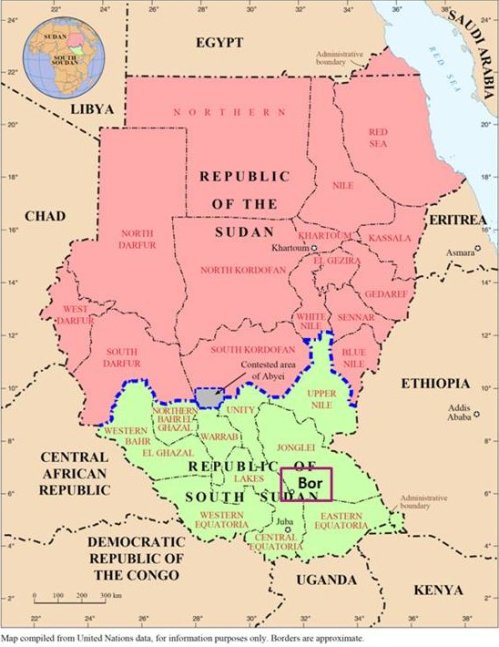

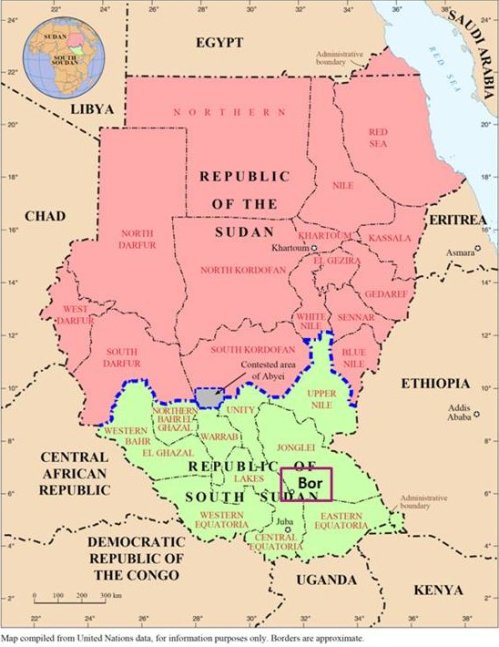

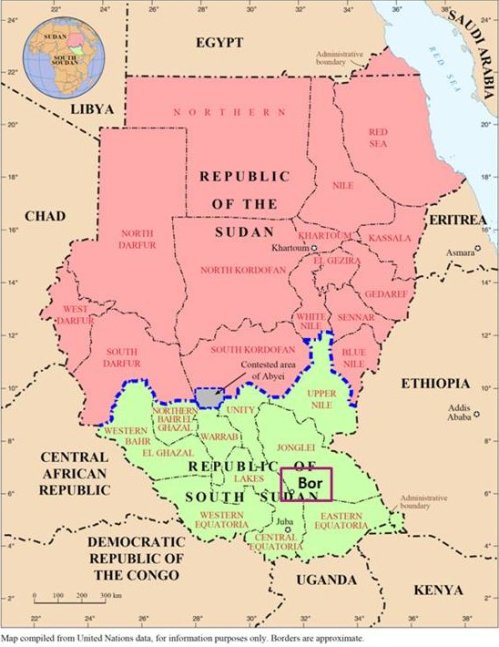

Three U.S. Osprey aircraft were hit by rebel fire in South Sudan on Saturday during an evacuation operation for American citizens. The Americans were being evacuated from the town of Bor, in the southern region of South Sudan near the capital of Juba. Four U.S. service members (presumably Marines) were injured when the aircraft took fire, and had to be transported via Uganda to Kenya for treatment.

South Sudan has had internal conflict since declaring its independence and obtaining recognition of statehood in July 2011. Fighting flared up this month, by various reports due to a coup attempt, or to an ethnic dispute between Dinka and Nuer members of the presidential guard. Former vice president Riek Machar, a Nuer, is at the head of a rebel faction now controlling part of the country (including Bor), and is accused by the head of the recognized government, Salva Kiir Mayardit (referred to as Kiir), of attempting the coup. Kiir is a Dinka who was a long-time John Garang loyalist with the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). In Machar’s checkered history of rebel leadership, over the last two-plus decades, he has agreed to various levels of temporary alliance with the Garang SPLA and the Sudanese government in Khartoum – the latter of which has for years had close relations with Iran.

The future has looked difficult for the fledgling nation of South Sudan from the beginning. South Sudan is land-locked, and heavily dependent on the Nile, which flows to the sea northward through Sudan. South Sudan has substantial oil reserves, but the refineries are in Sudan, and some of the South’s oil territories (as well as other lands) are disputed with Sudan. Much remains unsettled.

These are by no means the extent of South Sudan’s problems, however. Ethnic divisions have made the area very hard to unify. But the decades of determination shown by Garang and his evanescent SPLA coalition, which formed the core of the South Sudanese government, were prompted by the brutality of the Islamic regime in Khartoum. That regime, now led by Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, has periodically engaged in attempts at “ethnic cleansing” against the southern tribes, who are primarily a mix of Christians and adherents of local animist religions. (Kiir is a Catholic, and Machar was raised a Presbyterian.)

The Bashir regime in Khartoum has had extensive ties to Iran, and has been designated by the United States as a state sponsor of terrorism since 1993. In the last couple of years, Iran’s activities have stepped up in Sudan considerably, including a series of port visits by Iranian warships deployed for the antipiracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, as well as the delivery and transshipment of arms bound for Hamas, up north in Gaza. In October 2012, Israeli jets attacked an arms factory in southern Khartoum from which it was suspected that arms were being sent to Hamas; this post has a nice summary of the long list of Iranian activities in Sudan up through January 2013.

Following a December 2012 claim that Iran would develop a naval base in Sudan, on the Red Sea, reporting in 2013 has alluded, if somewhat vaguely, to a ramp-up in this effort. (See here and here, for example; for the very detailed summary here, I have been unable to find substantial corroboration from other sources. The information may be valid. However, a comparison of satellite imagery of Port Sudan from 2011 and 2013 – do a current Google Earth search for the latter – doesn’t seem to turn up evidence of new construction or other changes in the port complex. This doesn’t mean Iran isn’t using the port, nor does it mean Iran isn’t constructing a naval base somewhere else on the Sudanese coast. It does, however, make it hard to confirm the thesis of the Oilprice/GIS article that Sudan and the Iranians are worried about construction in Port Sudan being spied on. FWIW, I don’t find evidence of new construction at any other likely spot along Sudan’s coastline.)

In any case, the connections between Iran and Sudan are well known and established. China is South Sudan’s biggest trading partner, investing in her oil industry and buying most of her oil – but is also a long-time patron of Sudan. The main arms supplier of the insurgents in South Sudan is the government of Sudan – and the arms suppliers of the government of Sudan are Iran and China.

That won’t come as a shock to anyone, I know. It’s a reminder, however, of the kind of business both nations routinely do in this part of the world, and in particular, of Iran’s penchant for sowing discord and spreading the sponsorship of terrorism. This Iran will not behave better when she has a nuclear deterrent to wield against her neighbors, or the United States.

Consider, moreover, that a V-22 Osprey would stand out like a sore thumb in South Sudan. Quite obviously, it would not be a poor nation’s aircraft, or belong to any of the local militaries or factions. It is a very bad sign, that rebels in Bor felt they had the latitude to shoot at our aircraft – and not just a round or two, but enough to inflict damage on three of four aircraft, and cause injury to crewmembers. The exact circumstances of the incident haven’t been clarified; e.g., whether the aircraft were in the vicinity of a landing area, or were fired on while they were airborne in open country. But in all likelihood, it was clear to the attackers that they were firing on foreign aircraft that were not involved in their fight. In fact, it’s likely that they knew the aircraft were American.

I doubt, frankly, that our military planned this “NEO” – non-combatant evacuation operation – with the assumption that it would be non-permissive; that is, that it would come under attack. This was probably a surprise to us. What it should be is a lesson to us (as Benghazi should have been). When America is not keeping a steady strain on the lines of stabilizing power, instability starts to kick in very quickly. It doesn’t take long for it to come back on us.

J.E. Dyer’s articles have appeared at Hot Air, Commentary’s “contentions,” Patheos, The Daily Caller, The Jewish Press, and The Weekly Standard online. She also writes for the new blog Liberty Unyielding.

The future has looked difficult for the fledgling nation of South Sudan from the beginning. South Sudan is land-locked, and heavily dependent on the Nile, which flows to the sea northward through Sudan. South Sudan has substantial oil reserves, but the refineries are in Sudan, and some of the South’s oil territories (as well as other lands) are disputed with Sudan. Much remains unsettled.

These are by no means the extent of South Sudan’s problems, however. Ethnic divisions have made the area very hard to unify. But the decades of determination shown by Garang and his evanescent SPLA coalition, which formed the core of the South Sudanese government, were prompted by the brutality of the Islamic regime in Khartoum. That regime, now led by Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, has periodically engaged in attempts at “ethnic cleansing” against the southern tribes, who are primarily a mix of Christians and adherents of local animist religions. (Kiir is a Catholic, and Machar was raised a Presbyterian.)

The Bashir regime in Khartoum has had extensive ties to Iran, and has been designated by the United States as a state sponsor of terrorism since 1993. In the last couple of years, Iran’s activities have stepped up in Sudan considerably, including a series of port visits by Iranian warships deployed for the antipiracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, as well as the delivery and transshipment of arms bound for Hamas, up north in Gaza. In October 2012, Israeli jets attacked an arms factory in southern Khartoum from which it was suspected that arms were being sent to Hamas; this post has a nice summary of the long list of Iranian activities in Sudan up through January 2013.

Following a December 2012 claim that Iran would develop a naval base in Sudan, on the Red Sea, reporting in 2013 has alluded, if somewhat vaguely, to a ramp-up in this effort. (See here and here, for example; for the very detailed summary here, I have been unable to find substantial corroboration from other sources. The information may be valid. However, a comparison of satellite imagery of Port Sudan from 2011 and 2013 – do a current Google Earth search for the latter – doesn’t seem to turn up evidence of new construction or other changes in the port complex. This doesn’t mean Iran isn’t using the port, nor does it mean Iran isn’t constructing a naval base somewhere else on the Sudanese coast. It does, however, make it hard to confirm the thesis of the Oilprice/GIS article that Sudan and the Iranians are worried about construction in Port Sudan being spied on. FWIW, I don’t find evidence of new construction at any other likely spot along Sudan’s coastline.)

In any case, the connections between Iran and Sudan are well known and established. China is South Sudan’s biggest trading partner, investing in her oil industry and buying most of her oil – but is also a long-time patron of Sudan. The main arms supplier of the insurgents in South Sudan is the government of Sudan – and the arms suppliers of the government of Sudan are Iran and China.

That won’t come as a shock to anyone, I know. It’s a reminder, however, of the kind of business both nations routinely do in this part of the world, and in particular, of Iran’s penchant for sowing discord and spreading the sponsorship of terrorism. This Iran will not behave better when she has a nuclear deterrent to wield against her neighbors, or the United States.

Consider, moreover, that a V-22 Osprey would stand out like a sore thumb in South Sudan. Quite obviously, it would not be a poor nation’s aircraft, or belong to any of the local militaries or factions. It is a very bad sign, that rebels in Bor felt they had the latitude to shoot at our aircraft – and not just a round or two, but enough to inflict damage on three of four aircraft, and cause injury to crewmembers. The exact circumstances of the incident haven’t been clarified; e.g., whether the aircraft were in the vicinity of a landing area, or were fired on while they were airborne in open country. But in all likelihood, it was clear to the attackers that they were firing on foreign aircraft that were not involved in their fight. In fact, it’s likely that they knew the aircraft were American.

I doubt, frankly, that our military planned this “NEO” – non-combatant evacuation operation – with the assumption that it would be non-permissive; that is, that it would come under attack. This was probably a surprise to us. What it should be is a lesson to us (as Benghazi should have been). When America is not keeping a steady strain on the lines of stabilizing power, instability starts to kick in very quickly. It doesn’t take long for it to come back on us.

J.E. Dyer’s articles have appeared at Hot Air, Commentary’s “contentions,” Patheos, The Daily Caller, The Jewish Press, and The Weekly Standard online. She also writes for the new blog Liberty Unyielding.

anese faction that shot at U.S. aircraft supplied by Iran,

Three U.S. Osprey aircraft were hit by rebel fire in South Sudan

on Saturday during an evacuation operation for American citizens. The

Americans were being evacuated from the town of Bor, in the southern

region of South Sudan near the capital of Juba. Four U.S. service

members (presumably Marines) were injured when the aircraft took fire,

and had to be transported via Uganda to Kenya for treatment.

South Sudan has had internal conflict since declaring its independence and obtaining recognition of statehood in July 2011. Fighting flared up this month, by various reports due to a coup attempt, or to an ethnic dispute between Dinka and Nuer members of the presidential guard. Former vice president Riek Machar, a Nuer, is at the head of a rebel faction now controlling part of the country (including Bor), and is accused by the head of the recognized government, Salva Kiir Mayardit (referred to as Kiir), of attempting the coup. Kiir is a Dinka who was a long-time John Garang loyalist with the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). In Machar’s checkered history of rebel leadership, over the last two-plus decades, he has agreed to various levels of temporary alliance with the Garang SPLA and the Sudanese government in Khartoum – the latter of which has for years had close relations with Iran.

The future has looked difficult for the fledgling nation of South Sudan from the beginning. South Sudan is land-locked, and heavily dependent on the Nile, which flows to the sea northward through Sudan. South Sudan has substantial oil reserves, but the refineries are in Sudan, and some of the South’s oil territories (as well as other lands) are disputed with Sudan. Much remains unsettled.

These are by no means the extent of South Sudan’s problems, however. Ethnic divisions have made the area very hard to unify. But the decades of determination shown by Garang and his evanescent SPLA coalition, which formed the core of the South Sudanese government, were prompted by the brutality of the Islamic regime in Khartoum. That regime, now led by Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, has periodically engaged in attempts at “ethnic cleansing” against the southern tribes, who are primarily a mix of Christians and adherents of local animist religions. (Kiir is a Catholic, and Machar was raised a Presbyterian.)

The Bashir regime in Khartoum has had extensive ties to Iran, and has been designated by the United States as a state sponsor of terrorism since 1993. In the last couple of years, Iran’s activities have stepped up in Sudan considerably, including a series of port visits by Iranian warships deployed for the antipiracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, as well as the delivery and transshipment of arms bound for Hamas, up north in Gaza. In October 2012, Israeli jets attacked an arms factory in southern Khartoum from which it was suspected that arms were being sent to Hamas; this post has a nice summary of the long list of Iranian activities in Sudan up through January 2013.

Following a December 2012 claim that Iran would develop a naval base in Sudan, on the Red Sea, reporting in 2013 has alluded, if somewhat vaguely, to a ramp-up in this effort. (See here and here, for example; for the very detailed summary here, I have been unable to find substantial corroboration from other sources. The information may be valid. However, a comparison of satellite imagery of Port Sudan from 2011 and 2013 – do a current Google Earth search for the latter – doesn’t seem to turn up evidence of new construction or other changes in the port complex. This doesn’t mean Iran isn’t using the port, nor does it mean Iran isn’t constructing a naval base somewhere else on the Sudanese coast. It does, however, make it hard to confirm the thesis of the Oilprice/GIS article that Sudan and the Iranians are worried about construction in Port Sudan being spied on. FWIW, I don’t find evidence of new construction at any other likely spot along Sudan’s coastline.)

In any case, the connections between Iran and Sudan are well known and established. China is South Sudan’s biggest trading partner, investing in her oil industry and buying most of her oil – but is also a long-time patron of Sudan. The main arms supplier of the insurgents in South Sudan is the government of Sudan – and the arms suppliers of the government of Sudan are Iran and China.

That won’t come as a shock to anyone, I know. It’s a reminder, however, of the kind of business both nations routinely do in this part of the world, and in particular, of Iran’s penchant for sowing discord and spreading the sponsorship of terrorism. This Iran will not behave better when she has a nuclear deterrent to wield against her neighbors, or the United States.

Consider, moreover, that a V-22 Osprey would stand out like a sore thumb in South Sudan. Quite obviously, it would not be a poor nation’s aircraft, or belong to any of the local militaries or factions. It is a very bad sign, that rebels in Bor felt they had the latitude to shoot at our aircraft – and not just a round or two, but enough to inflict damage on three of four aircraft, and cause injury to crewmembers. The exact circumstances of the incident haven’t been clarified; e.g., whether the aircraft were in the vicinity of a landing area, or were fired on while they were airborne in open country. But in all likelihood, it was clear to the attackers that they were firing on foreign aircraft that were not involved in their fight. In fact, it’s likely that they knew the aircraft were American.

I doubt, frankly, that our military planned this “NEO” – non-combatant evacuation operation – with the assumption that it would be non-permissive; that is, that it would come under attack. This was probably a surprise to us. What it should be is a lesson to us (as Benghazi should have been). When America is not keeping a steady strain on the lines of stabilizing power, instability starts to kick in very quickly. It doesn’t take long for it to come back on us.

J.E. Dyer’s articles have appeared at Hot Air, Commentary’s “contentions,” Patheos, The Daily Caller, The Jewish Press, and The Weekly Standard online. She also writes for the new blog Liberty Unyielding.

South Sudan has had internal conflict since declaring its independence and obtaining recognition of statehood in July 2011. Fighting flared up this month, by various reports due to a coup attempt, or to an ethnic dispute between Dinka and Nuer members of the presidential guard. Former vice president Riek Machar, a Nuer, is at the head of a rebel faction now controlling part of the country (including Bor), and is accused by the head of the recognized government, Salva Kiir Mayardit (referred to as Kiir), of attempting the coup. Kiir is a Dinka who was a long-time John Garang loyalist with the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). In Machar’s checkered history of rebel leadership, over the last two-plus decades, he has agreed to various levels of temporary alliance with the Garang SPLA and the Sudanese government in Khartoum – the latter of which has for years had close relations with Iran.

The future has looked difficult for the fledgling nation of South Sudan from the beginning. South Sudan is land-locked, and heavily dependent on the Nile, which flows to the sea northward through Sudan. South Sudan has substantial oil reserves, but the refineries are in Sudan, and some of the South’s oil territories (as well as other lands) are disputed with Sudan. Much remains unsettled.

These are by no means the extent of South Sudan’s problems, however. Ethnic divisions have made the area very hard to unify. But the decades of determination shown by Garang and his evanescent SPLA coalition, which formed the core of the South Sudanese government, were prompted by the brutality of the Islamic regime in Khartoum. That regime, now led by Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, has periodically engaged in attempts at “ethnic cleansing” against the southern tribes, who are primarily a mix of Christians and adherents of local animist religions. (Kiir is a Catholic, and Machar was raised a Presbyterian.)

The Bashir regime in Khartoum has had extensive ties to Iran, and has been designated by the United States as a state sponsor of terrorism since 1993. In the last couple of years, Iran’s activities have stepped up in Sudan considerably, including a series of port visits by Iranian warships deployed for the antipiracy mission in the Gulf of Aden, as well as the delivery and transshipment of arms bound for Hamas, up north in Gaza. In October 2012, Israeli jets attacked an arms factory in southern Khartoum from which it was suspected that arms were being sent to Hamas; this post has a nice summary of the long list of Iranian activities in Sudan up through January 2013.

Following a December 2012 claim that Iran would develop a naval base in Sudan, on the Red Sea, reporting in 2013 has alluded, if somewhat vaguely, to a ramp-up in this effort. (See here and here, for example; for the very detailed summary here, I have been unable to find substantial corroboration from other sources. The information may be valid. However, a comparison of satellite imagery of Port Sudan from 2011 and 2013 – do a current Google Earth search for the latter – doesn’t seem to turn up evidence of new construction or other changes in the port complex. This doesn’t mean Iran isn’t using the port, nor does it mean Iran isn’t constructing a naval base somewhere else on the Sudanese coast. It does, however, make it hard to confirm the thesis of the Oilprice/GIS article that Sudan and the Iranians are worried about construction in Port Sudan being spied on. FWIW, I don’t find evidence of new construction at any other likely spot along Sudan’s coastline.)

In any case, the connections between Iran and Sudan are well known and established. China is South Sudan’s biggest trading partner, investing in her oil industry and buying most of her oil – but is also a long-time patron of Sudan. The main arms supplier of the insurgents in South Sudan is the government of Sudan – and the arms suppliers of the government of Sudan are Iran and China.

That won’t come as a shock to anyone, I know. It’s a reminder, however, of the kind of business both nations routinely do in this part of the world, and in particular, of Iran’s penchant for sowing discord and spreading the sponsorship of terrorism. This Iran will not behave better when she has a nuclear deterrent to wield against her neighbors, or the United States.

Consider, moreover, that a V-22 Osprey would stand out like a sore thumb in South Sudan. Quite obviously, it would not be a poor nation’s aircraft, or belong to any of the local militaries or factions. It is a very bad sign, that rebels in Bor felt they had the latitude to shoot at our aircraft – and not just a round or two, but enough to inflict damage on three of four aircraft, and cause injury to crewmembers. The exact circumstances of the incident haven’t been clarified; e.g., whether the aircraft were in the vicinity of a landing area, or were fired on while they were airborne in open country. But in all likelihood, it was clear to the attackers that they were firing on foreign aircraft that were not involved in their fight. In fact, it’s likely that they knew the aircraft were American.

I doubt, frankly, that our military planned this “NEO” – non-combatant evacuation operation – with the assumption that it would be non-permissive; that is, that it would come under attack. This was probably a surprise to us. What it should be is a lesson to us (as Benghazi should have been). When America is not keeping a steady strain on the lines of stabilizing power, instability starts to kick in very quickly. It doesn’t take long for it to come back on us.

J.E. Dyer’s articles have appeared at Hot Air, Commentary’s “contentions,” Patheos, The Daily Caller, The Jewish Press, and The Weekly Standard online. She also writes for the new blog Liberty Unyielding.

No comments:

Post a Comment