Vol. 12, No. 23 24 October 2012

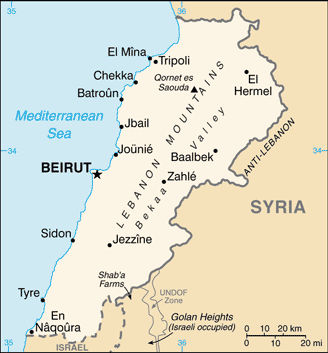

Map: Al-Manar

Hizbullah has been using heavy weapons including artillery and

rockets in the Qusayr area in an effort to dislodge FSA forces from Abu

Hori, Al Nahiyah, Sakarjah and Al Burhaniyah, as it seeks to prevent the

FSA from enjoying direct territorial continuity with Lebanon. It was

even reported that Hizbullah has taken control of Syrian villages and

towns in that same area such as Zeyta, Hawik, El Hamam, Al Safsafah, Al

Fadiliyah and the groves of Al Nazariyah. Hizbullah currently claims

control of 18 villages along the widest part of the Orontes River Basin:

Bab al-Hawa, Wadi Hanna, Rabla, Matraba, Al Jadaliyya, Balluza, Al

Huwayik, Ghawgharan, Al Summaqiyyat, Al Hamam, Al Safiyyah, Zeita, Al

Fadiliyya, Al Qarniyya, Al Misriyya, Dibbin, Al Suwayidyya and Al Hush.

The most Hizbullah activity in Syria has occurred in this area,

particularly around the border town of Al Qusayr.2

Map: Al-Manar

Hizbullah has been using heavy weapons including artillery and

rockets in the Qusayr area in an effort to dislodge FSA forces from Abu

Hori, Al Nahiyah, Sakarjah and Al Burhaniyah, as it seeks to prevent the

FSA from enjoying direct territorial continuity with Lebanon. It was

even reported that Hizbullah has taken control of Syrian villages and

towns in that same area such as Zeyta, Hawik, El Hamam, Al Safsafah, Al

Fadiliyah and the groves of Al Nazariyah. Hizbullah currently claims

control of 18 villages along the widest part of the Orontes River Basin:

Bab al-Hawa, Wadi Hanna, Rabla, Matraba, Al Jadaliyya, Balluza, Al

Huwayik, Ghawgharan, Al Summaqiyyat, Al Hamam, Al Safiyyah, Zeita, Al

Fadiliyya, Al Qarniyya, Al Misriyya, Dibbin, Al Suwayidyya and Al Hush.

The most Hizbullah activity in Syria has occurred in this area,

particularly around the border town of Al Qusayr.2

The Syrian rebel forces have displaced the occupants in order to create a smuggling link from the Homs countryside to Wadi Khaled and north Lebanon, which tends to back the Syrian uprising. This forced displacement prompted Hizbullah to confront the opposition with heavy force, driving the Free Syrian Army to focus their smuggling on the area between Masharih al-Qaa and Upper Aarsal.

Hizbullah officials have repeatedly denied that their group has troops on the ground in Syria. However, on October 9, Hizbullah had to face an unanticipated event: Ali Hussein Nassif (alias Abu Abbas), commander and coordinator of Hizbullah’s forces in Syria, was killed in Qusayr, deep in Syrian territory, prompting further speculation about Hizbullah’s role in the fighting. According to reports from that area, Hizbullah suffered severe losses to the FSA, which succeeded in repelling Hizbullah attacks combined with Syrian Air Force strikes against the strategic town of Joussiyeh.

Abu Abbas was treated like a martyr and a ceremonious funeral was held in his hometown of Boudiyah (on the border with Syria). In his eulogy, Mohammad Yazbek, head of the Judiciary Council and member of the Shura Council (Hizbullah’s highest decision-making authority), said that Abu Abbas had died in Syria protecting Lebanese citizens who live there (!). In his own words, Yazbek described those Lebanese as “oppressed and as such who have been abandoned by the state (Lebanon) and government” – a typical Shiite wording used to describe the Shiites living in Lebanon.3

According to local sources in the Homs countryside, Hizbullah and the Syrian opposition have 5,000 fighters each. Both sides have kidnapped members of their rivals, and there have been three rounds of fighting between clusters of villages since September 2011. The Free Syrian Army accused Hizbullah of “occupying” six Syrian towns near the Lebanese-Syrian border including Joussiyeh and Al Qusayr, where the Hizbullah commander found his death.

Greater Lebanon was created by France to be a “safe haven” for the Maronite population of Mt. Lebanon, an area with a Maronite majority that had enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy under the Ottoman Empire. However, in addition to Mount Lebanon, Greater Lebanon included other, mainly Muslim, regions that were not part of the Maronite administrative province; hence, the word “greater.” Those regions correspond today to north Lebanon, south Lebanon, the Beqaa Valley, and Beirut. The capital of Greater Lebanon was Beirut. The new state was granted a flag merging the French flag with the cedar of Mt. Lebanon.

The French Mandatory authorities delineated the Lebanon-Syria border in the years following the creation of Greater Lebanon in 1920, drawing detailed maps of the frontier in 1934. The border was supposed to follow the perimeters of four ex-Ottoman sub-provinces: Akkar in the north, Baalbek in the east, and Hasbayya and Rashayya in the southeast. For the sake of convenience, the boundaries were defined by the geographical features of the Nahr al-Kabir in the north and the peaks of the Anti-Lebanon mountain range and Mount Hermon in the east.4

But these natural boundaries often conflicted with property rights, where Lebanese-owned land ended up inside Syria and vice versa, and with local demographics. For example, the village of Tufayl, which longitudinally lies just east of central Damascus, is connected to the Bekaa Valley by a narrow finger of Lebanese territory that projects eastward over the Anti-Lebanon range and into the semi-desert north of the Syrian capital. Tufayl was included in Lebanon due to its population being Shiite, therefore more closely connected to their co-religionists in the Bekaa than the Sunnis and Aramaic-speaking Greek Catholics who are their immediate neighbors in Syria.5

Muslims in Greater Lebanon rejected the new state upon its creation. The continuous Muslim demand for reunification with Syria eventually brought about an armed conflict between Muslims and Christians in 1958 when Muslim Lebanese wanted to join the newly proclaimed United Arab Republic, while Christians were strongly opposed.

In the decades after Lebanon and Syria gained independence in the 1940s, both countries formed several committees to settle border disputes, all of them unsuccessful,6 and the notoriously porous border remained a source of contention between Lebanon and Syria:

Hizbullah’s direct participation in the fighting in Syria has created a precedent: For the first time since its establishment, Hizbullah is “exporting” its military know-how and might for use against Arab neighbors, in order to respond to Tehran’s strategic scheme to protect the Assad regime from falling. But by doing so, Hizbullah has alienated the Sunni majority in Syria (and also in Lebanon) which, in the event that Assad falls, will probably strive to make Hizbullah bear the consequences of its support for the Alawite regime. Signals in this direction are already being sent in the media, while Hizbullah itself has stepped up its preparations in the Dahiyah area of south Beirut in anticipation of such consequences. It would be fair to assess that in case Assad’s regime falls, Hizbullah will also have to fight for its life in the Lebanese context. For this reason, it seems that Hizbullah’s involvement in the fighting in Syria is crucial. Hizbullah has to win the war there in order to survive in Lebanon.

Finally, Hizbullah has been fighting for years to prove its “Lebanese” credentials. Fighting alongside the Alawite regime has turned Hizbullah back into what it really is: just another Lebanese armed militia, a Shiite army at the service of its patrons, sponsors, and protectors in Tehran. Its aims remain sectarian and not national or supra-national – namely, fighting a Shiite war. This is far from what it claimed to be – a pan-Islamic movement to fight Israel and the West.

- The fighting in Syria has already spilled over the border into Lebanon, threatening the fragile sectarian balance holding that country together. Cross-border attacks have become customary, with the Syrian Army shelling and shooting into Lebanese villages that it says are harboring Syrian rebels.

- Across from El Hermel in northeastern Lebanon and inside Syrian territory, a string of villages inhabited by Shiites has been clashing with majority-Sunni villages that back the Syrian opposition forces in the countryside of Qusayr, on the outskirts of Homs. Hizbullah is interfering directly and militarily in Qusayr under the pretext of protecting the Shiite villages in the area. It currently claims control of 18 villages along the widest part of the Orontes River Basin.

- The French Mandatory authorities delineated the Lebanon-Syria border in the years following the creation of Greater Lebanon in 1920, but the border was never finalized. What is happening on the ground could be called de facto demarcation since Hizbullah has a presence in the string of Shiite villages (annexing them de facto to Lebanon), while the Free Syrian Army is present in most Sunni villages, thus annexing them to Syria.

- Hizbullah appears to be carving out a 20-kilometer (12-mile) border corridor to the Syrian Alawite enclave on the coast. Hizbullah appears to be seeking to control strategic access to the Orontes River Basin in Syria and Lebanon to form a contiguous Alawite-Shiite mini-state. Yet the Shiite belt would likely face a major challenge from Sunnis on both sides of the border.

- For the first time, Hizbullah is “exporting” its military know-how and might for use against Arab neighbors, in order to respond to Tehran’s strategic scheme to protect the Assad regime from falling. But by doing so, Hizbullah has alienated the Sunni majority in Syria and also in Lebanon. It would be fair to assess that in case Assad’s regime falls, Hizbullah will also have to fight for its life in the Lebanese context.

- Hizbullah has been fighting for years to prove its “Lebanese” credentials. Fighting alongside the Alawite regime has turned Hizbullah back into what it really is: just another Lebanese armed militia, a Shiite army at the service of its patrons, sponsors, and protectors in Tehran.

The Syrian Conflict Spills into Lebanon

As the fighting in Syria intensifies, the conflict has already spilled over the border into Lebanon, threatening the fragile sectarian balance holding that country together and sparking yet another blood-spattered internal conflict. Although the clashes are still limited to the ill-defined border areas between the two countries and in the northern Lebanese town of Tripoli, still, the latest car bombing in Beirut on October 19 (the first since 2008) which targeted senior Lebanese intelligence official Wissam al-Hassan, who led the investigation that implicated Syria and Hizbullah in the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, was most probably the result of Syrian–Hizbullah cooperation and could herald an expansion of the domestic Lebanese conflict between supporters and opponents of the Assad regime. Hassan was the brains behind the uncovering of a bomb plot that led to the arrest and indictment in August 2012 of former Lebanese minister Michel Samaha, an ally of Syrian President Bashar Assad, in a setback for Damascus and its Lebanese allies including Hizbullah.

These events are serious enough to cause alarm among

Lebanese politicians and the public that the military situation might

escalate and the country might find itself in civil strife for

sheltering opposition rebels within its borders.

Since the beginning of the rebellion in Syria, the

Syrian regime has repeatedly requested that Lebanon secure its borders

from smugglers, to no avail. As a result, cross-border attacks have

become customary, with the Syrian Army shelling and shooting into

Lebanese villages that it says are harboring Syrian rebels. The Syrian

army has strengthened its positions along Lebanon’s northeastern border

to prevent weapons smuggling and the infiltration of fighters. Syria’s

opposition groups have indeed made use of this largely porous territory.

Many of those fleeing from Syria or wounded in the violence have been

brought across the border into Lebanon. Since the uprising began, Syrian

security forces have slipped into various border towns and villages in

pursuit of what they call “armed terrorist groups.”

The Lebanese government has made numerous complaints to the Syrian

authorities but the incursions have not stopped. Lebanese President

Michel Suleiman asked his foreign minister in July 2012 to send an

official letter of complaint to the Syrian ambassador in Beirut, but the

complaint got tangled up in sectarian and regional alliances, a common

feature of Lebanese politics. Lebanon’s foreign minister, Adnan Mansour,

is a member of Amal, a Shiite political party that is a strong

supporter of the Syrian government, and the letter he ultimately sent to

the ambassador fell far short of a formal complaint.1

Lebanon’s northeastern

border with Syria was once calm, with smugglers regularly ferrying food

and fuel between the two countries. But now the dynamics have changed:

Fighters and weapons have replaced consumer goods as the hot

commodities, and fighting erupts frequently in the once quiet border

villages. Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters easily cross into the country

and can move freely to carry out operations or move men and arms. The

region befits these activities with its heavy tree cover, borders that

are not clearly demarcated, and Sunni residents who are generally

supportive of their aims.

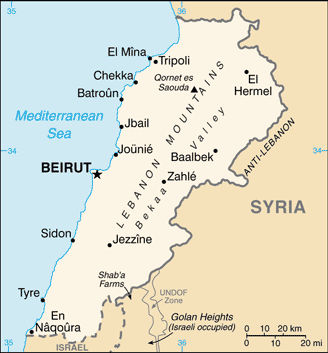

Map: CIA Factbook

Flashpoint Shiite Villages Inside Syria

However, across from El

Hermel in northeastern Lebanon and inside Syrian territory, a string of

villages inhabited by Shiites has been clashing with majority-Sunni

villages that back the Syrian opposition forces in the countryside of

Qusayr, on the outskirts of Homs, and there has been a series of mutual

kidnappings between the groups. Hizbullah is interfering directly and

militarily in Qusayr under the pretext of protecting the Shiite villages

in the area. Hizbullah has deployed its combatants in the upper Brital

villages of Tfeil and Maaraboun, and it also has men in Zabadani and

Sarghaya, where there are regular clashes between the rebel Free Syrian

Army and Assad’s troops. In 23 Shiite villages (mostly inhabited by

members of the Hamadeh, Jaafar and Zeaiter clans) which once housed

21,000-30,000 people, less than half of the original residents remain;

the rest were forced out or fled. In fact, Hizbullah forces have been

assigned to protect and control the Orontes River Basin – a strategic

area that links the Syrian hinterland to the port of Tripoli in northern

Lebanon. Control of this area would, of course, prevent the FSA from

smuggling arms, ammunition, and fighters into Syria from Lebanon.

Map: Al-Manar

Map: Al-ManarThe Syrian rebel forces have displaced the occupants in order to create a smuggling link from the Homs countryside to Wadi Khaled and north Lebanon, which tends to back the Syrian uprising. This forced displacement prompted Hizbullah to confront the opposition with heavy force, driving the Free Syrian Army to focus their smuggling on the area between Masharih al-Qaa and Upper Aarsal.

Hizbullah officials have repeatedly denied that their group has troops on the ground in Syria. However, on October 9, Hizbullah had to face an unanticipated event: Ali Hussein Nassif (alias Abu Abbas), commander and coordinator of Hizbullah’s forces in Syria, was killed in Qusayr, deep in Syrian territory, prompting further speculation about Hizbullah’s role in the fighting. According to reports from that area, Hizbullah suffered severe losses to the FSA, which succeeded in repelling Hizbullah attacks combined with Syrian Air Force strikes against the strategic town of Joussiyeh.

Abu Abbas was treated like a martyr and a ceremonious funeral was held in his hometown of Boudiyah (on the border with Syria). In his eulogy, Mohammad Yazbek, head of the Judiciary Council and member of the Shura Council (Hizbullah’s highest decision-making authority), said that Abu Abbas had died in Syria protecting Lebanese citizens who live there (!). In his own words, Yazbek described those Lebanese as “oppressed and as such who have been abandoned by the state (Lebanon) and government” – a typical Shiite wording used to describe the Shiites living in Lebanon.3

According to local sources in the Homs countryside, Hizbullah and the Syrian opposition have 5,000 fighters each. Both sides have kidnapped members of their rivals, and there have been three rounds of fighting between clusters of villages since September 2011. The Free Syrian Army accused Hizbullah of “occupying” six Syrian towns near the Lebanese-Syrian border including Joussiyeh and Al Qusayr, where the Hizbullah commander found his death.

The Lebanon-Syria Border Was Never Finalized

No doubt, the cross-border conflict also stems from the fact that the border remains in dispute in numerous places. Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan conceded that “there seems to be no official record of a formal international boundary agreement between Lebanon and the Syrian Arab Republic.” The continued ambiguity over the Lebanon-Syria border is due to the indifference of the Lebanese state to its impoverished frontier regions and Syria’s reluctance to accept the notion of a separate Lebanon. Syria has always considered Lebanon to be a province of Syria.Greater Lebanon was created by France to be a “safe haven” for the Maronite population of Mt. Lebanon, an area with a Maronite majority that had enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy under the Ottoman Empire. However, in addition to Mount Lebanon, Greater Lebanon included other, mainly Muslim, regions that were not part of the Maronite administrative province; hence, the word “greater.” Those regions correspond today to north Lebanon, south Lebanon, the Beqaa Valley, and Beirut. The capital of Greater Lebanon was Beirut. The new state was granted a flag merging the French flag with the cedar of Mt. Lebanon.

The French Mandatory authorities delineated the Lebanon-Syria border in the years following the creation of Greater Lebanon in 1920, drawing detailed maps of the frontier in 1934. The border was supposed to follow the perimeters of four ex-Ottoman sub-provinces: Akkar in the north, Baalbek in the east, and Hasbayya and Rashayya in the southeast. For the sake of convenience, the boundaries were defined by the geographical features of the Nahr al-Kabir in the north and the peaks of the Anti-Lebanon mountain range and Mount Hermon in the east.4

But these natural boundaries often conflicted with property rights, where Lebanese-owned land ended up inside Syria and vice versa, and with local demographics. For example, the village of Tufayl, which longitudinally lies just east of central Damascus, is connected to the Bekaa Valley by a narrow finger of Lebanese territory that projects eastward over the Anti-Lebanon range and into the semi-desert north of the Syrian capital. Tufayl was included in Lebanon due to its population being Shiite, therefore more closely connected to their co-religionists in the Bekaa than the Sunnis and Aramaic-speaking Greek Catholics who are their immediate neighbors in Syria.5

Muslims in Greater Lebanon rejected the new state upon its creation. The continuous Muslim demand for reunification with Syria eventually brought about an armed conflict between Muslims and Christians in 1958 when Muslim Lebanese wanted to join the newly proclaimed United Arab Republic, while Christians were strongly opposed.

In the decades after Lebanon and Syria gained independence in the 1940s, both countries formed several committees to settle border disputes, all of them unsuccessful,6 and the notoriously porous border remained a source of contention between Lebanon and Syria:

- There is at least 460 km2 of Lebanon occupied by Syria.

- There are dozens of smuggling passages in operation, all used to import goods and infiltrate foreign fighters and weapons.

- There are numerous Syrian Army camps inside Lebanese territory.7

The Free Syrian Army and Hizbullah Move to Protect Their Interests

In late 2008, Lebanon and Syria made the historic decision to establish diplomatic relations for the first time, but the border issue was left open. The beginning of the rebellion against Assad put an end to any possible cooperation for the time being on the issue.

Left with no alternative, the FSA and Hizbullah have

decided to act in order to protect their interests. In fact, what is

happening on the ground could in a way be called de facto demarcation since Hizbullah has a presence in the string of Shiite villages (annexing them de facto

to Lebanon), while the FSA is present in most Sunni villages, thus

annexing them to Syria. The fighting is therefore taking place in the

mixed villages or in those which are vital for maintaining geographical

homogeneity in the Sunni and Shiite areas. When the fighting ends, it is

likely that the demarcation of the ill-defined border will have been

facilitated by the events of today.

Hizbullah appears to have a contingency plan to carve out and defend a

20-kilometer (12-mile) border corridor to the Syrian Alawite enclave on

the coast. This is a difficult endeavor because Hizbullah does not

exercise authority in Sunni-dominated northern Lebanon. Instead,

Hizbullah appears to be seeking to control strategic access to the

Orontes River Basin in Syria and Lebanon to form a contiguous

Alawite-Shiite mini-state. Controlling the bulge of the river basin

would theoretically allow Hizbullah to pool resources with an Alawite

enclave in the northern Bekaa while the organization attempts to hold

its ground in the southern Beirut suburbs and southern Lebanon.8

The purported plan to build this sectarian fortress is fraught with

complications, especially since the Shiite belt would likely face a

major challenge from Sunnis on both sides of the border. But in

contingency planning, one must hope for the best and prepare for the

worst. Hizbullah is evidently doing just that.Hizbullah’s direct participation in the fighting in Syria has created a precedent: For the first time since its establishment, Hizbullah is “exporting” its military know-how and might for use against Arab neighbors, in order to respond to Tehran’s strategic scheme to protect the Assad regime from falling. But by doing so, Hizbullah has alienated the Sunni majority in Syria (and also in Lebanon) which, in the event that Assad falls, will probably strive to make Hizbullah bear the consequences of its support for the Alawite regime. Signals in this direction are already being sent in the media, while Hizbullah itself has stepped up its preparations in the Dahiyah area of south Beirut in anticipation of such consequences. It would be fair to assess that in case Assad’s regime falls, Hizbullah will also have to fight for its life in the Lebanese context. For this reason, it seems that Hizbullah’s involvement in the fighting in Syria is crucial. Hizbullah has to win the war there in order to survive in Lebanon.

Finally, Hizbullah has been fighting for years to prove its “Lebanese” credentials. Fighting alongside the Alawite regime has turned Hizbullah back into what it really is: just another Lebanese armed militia, a Shiite army at the service of its patrons, sponsors, and protectors in Tehran. Its aims remain sectarian and not national or supra-national – namely, fighting a Shiite war. This is far from what it claimed to be – a pan-Islamic movement to fight Israel and the West.

* * *

Notes

1. Babak Dehghanpishch, “Lebanese Worry that Syria Army Might Escalate Attacks,” www.yalibnan.com, July 30, 2012

2. Louai Beshara, “ Hizbullah’s Contingency Planning,” AFP-Stratfor, 18 October 18, 2012.

3. Rashed Fayed, “Jihad? Ay Jihad!,” Al-Shafaf, October 9, 2012.

4. Nicholas Blanford, “Border Complications Promise Long Dispute,” Bitterlemons International, September 18, 2008, http://www.bitterlemons-international.org/inside.php?id=1002

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. “Lebanese-Syrian Borders: Fact-Finding Survey,” May 2007, nowlebanon.com

8. Beshara, op. cit.

No comments:

Post a Comment